Why do women leave academia after completing a PhD?

-

Sist oppdatert

22. mai 2023

-

Kategori

-

Tema

- Women in academia

- Leaky pipeline

- Women's career

The higher the academic level, the lower the percentage of women. It is a lose-lose game for female scientists and academia.

KNOWLEDGE AT KRISTIANIA: Women in academia

The proportion of women in academia progressively decreases with advancing career stages. This phenomenon is known as the «leaky pipeline», meaning that women are «leaking out» of the academic pipeline.

It affects all research fields. However, the problem is particularly accentuated within Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics – the STEM disciplines.

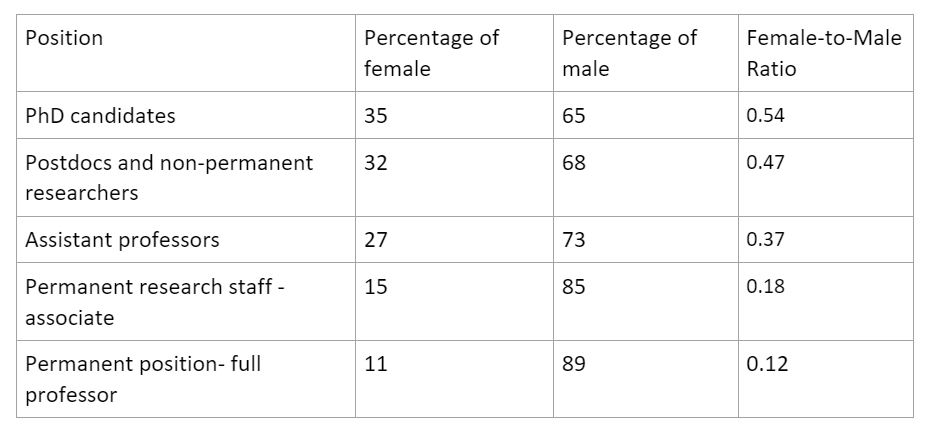

The number of female candidates dramatically decreases from master’s to PhD, and continues declining at the postdoc/researcher level, reaching the lowest point at full professorship.

The higher the level, the lower the percentage of women – it’s a lose-lose game

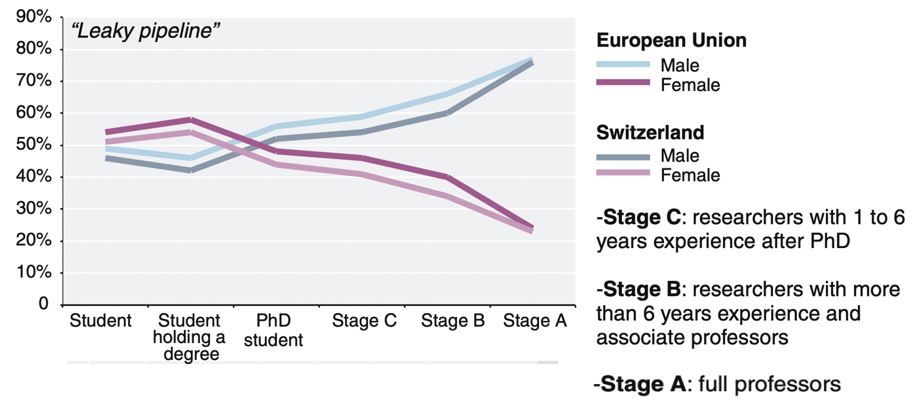

Although the number of female candidates reaching PhD-level is higher than the number of male candidates, the reduction slope for women in academia intensifies at the higher levels, as shown in the figure below.

It is the opposite for men.

So, we have two lines showing male and female numbers in the career path crossing each other, creating a further distance at the highest academic level, giving a scissor-shaped curve.

The numbers are different from one discipline and university to another. However, the slope remains.

Metaphorically, women are being cut away from the high end of the academic career development path. So the question is, are we losing something here?

The clear answer is: Yes.

And this is serious for several reasons:

- We lose the benefits of gender balance.

- It is against UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) objectives.

- It means we fail at equality and fairness.

- It represents a loss of talent and diversity in academic fields.

Why are we losing women from academia at the higher level?

Several factors cause this problem. There are biological factors, as well as cultural factors. Biologically, women have age limitations for fertility, which unfortunately tend to match the career development period in academia.

So, while young men aged 25-45 can focus on achieving success in their careers, especially at the PhD-level and after its completion, women must also consider maternity.

Women also tend to consider themselves more successful when they manage to foster several aspects of life in this short time; starting a family, giving birth to a suitable number of kids with good age differences, and raising them, while at the same time remaining healthy, youthful and physically attractive, as well as pursuing a successful career.

Society and culture tend to expect the same from a woman.

Men, on the other hand, are not to the same degree expected to expand the other aspects of life during this age period such as achieving “settled paternity” while pursuing a successful career at the top stages in academia.

While all researchers may face well-known syndromes such as imposter syndrome and depression, female researchers struggle to succeed in various areas of life during a relatively short time slot.

As a result, women often struggle to progress in their careers and are more likely to leave academia altogether at the last career development phases.

If academia itself is not the direct cause by actively pushing female researchers out through exaggerated expectations of publications, supervision, teaching, etc., academia is no doubt losing them. The numbers are clear.

Biology, society, and culture combined create the leaky pipeline problem for women in academia, resulting in the scissor-shaped curve, revealing the dramatic difference between male and female careers within academia.

What can be done?

Historically there have been many attempts at gender equality measures within many professional areas, with no exception in academia. One example is giving women priority when hiring in cases where two applicants have equal expertise.

However, academic women must gain competence, survive in academia, and apply to reach the hiring step. Hence, rather than waiting for a hiring opportunity, academia should create incentives that fit female researchers better to prevent them from “leaking out” of academia.

Apart from broadening the hiring strategies, the rules of promotion should be changed in order to keep valuable female researchers who are eager scientists for the future.

Considering that the biological, social, and cultural expectations are different for women and men, how can we justify the rules and processes being the same?

It is crucial to address this issue not only to provide equal opportunities for women but also to promote diversity and excellence in academic research and teaching.

Let’s not lose PhD women in academia, as they are the low-hanging fruits!

Author: Toktam Ramezanifarkhani, Associate professor, School of Economics, Innovation and Technology

References:

Fox, M. F. (2010). Gender, family characteristics, and publication productivity among scientists. Social Studies of Science, 40(5), 879-900.

Xie, Y., & Shauman, K. A. (2003). Women in science: Career processes and outcomes. Harvard University Press.

Dubois-Shaik, Farah, Bernard Fusulier, and Caroline Vincke. “A gendered pipeline typology in academia.” Gender and Precarious Research Careers. Routledge, 2018. 178-205.11:42

This text was published on forskning.no/sciencenorway.no on the 27th of June under the following heading: "Why do women leave academia after completing a PhD?".

We would love to hear from you:

Send your comments and questions regarding this article by e-mail to kunnskap@kristiania.no.

Siste nytt fra Kunnskap Kristiania

Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merSlik skjuler reklamen seg i hverdagen din

Hva skjer når du trykker “liker” på en video eller deler noe i sosiale medier? Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merDroner redder liv, men er også sårbare selv

Droner brukes i redningsarbeid og vedlikehold av infrastruktur. Hvordan skal vi beskytte dem mot hacking? Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merRolls-Royce-logikk kan gi tog som nesten aldri står

Tenk deg en verden der fly er i rute og sykehus driftes effektivt. Hvordan får vi det til? Kunnskap KristianiaLes mer

Kunnskap KristianiaLes merFem områder der kunstig intelligens kan påvirke livet ditt

Kunstig intelligens er kommet for å bli. Professor Jon Arild Johannessen skisserer noen fremtidsscenarier.