When political satire is no joke

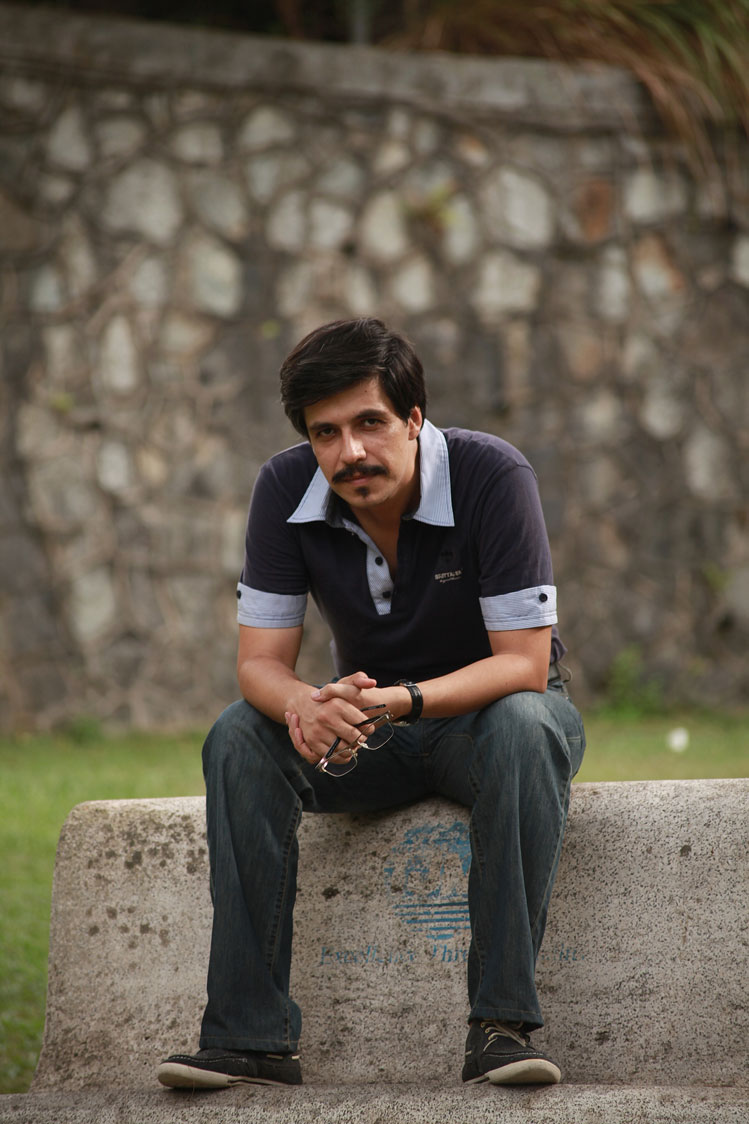

The Iranian scholar Dr. Mahmud Farjami has lived in exile since 2010, this past year in Oslo, working for Kristiania University College. Since childhood he has loved to tell jokes, but this quality has not always been appreciated. He was 9 the first time he was expelled from school.

Farjami’s crime was that he made the other kids in his class laugh. He carried around a little notebook full of numbers and keywords like “lady, dog, supermarket” to help him remember the jokes he made up. Despite this secretive strategy, the principal knew what he was up to. During elementary school he was punished several times.

Things got more and more serious as he got older. By the time he was in high school, innocent jokes had developed into skillful satire. Apart from school, he also had problems with his parents, some friends and certain officials.

Persian literature has a lot of irony, sometimes it is very harsh political satire.

“Persian literature has a lot of irony, sometimes it is very harsh political satire”, Farjami explains. “For example, the great poet Hafez [Editor’s note: 1315–1390 AD] is still worshiped by people in Iran.

At university Farjami studied computer science, philosophy and communication. He started working as a freelance journalist writing political satire for newspapers and magazines in Iran. In the early 2000’s Farjami got into building webpages and made one for himself. He became a well-known blogger, writing under the pen name MF for several years. Few knew his identity.

“One time a friend forwarded one of my satires to me. ‘Learn from this guy,’ he said. ‘MF writes so much better than you!’”

Red lines all around

In Farjami’s lifetime there has never been total freedom of speech in his home country, but he knew how to maneuver between what he calls “the red lines”.

“Here in Norway you can criticize everybody, but if you did that in Saudi Arabia you would get killed. Iran is somewhere between the two extremes. Iranians are Muslims, but they don’t care that much about Islam. In private we can make jokes about God and basically anything – just not in public. Same about politics!”

However, after the presidential election in 2009, the clerical regime tightened its grip. Three opposition candidates claimed the votes were manipulated and the election was rigged. People protested in the streets in what came to be called the Green Movement. Some dubbed the protests the Twitter Revolution, due to the massive use of Twitter and other social media to tell the rest of the world what was happening.

After the coup it got tighter and tighter. My website was shut down, my daily column in Tehran Today was banned and in the end I had no job.

“This was around my peak of popularity. After the coup it got tighter and tighter. My website was shut down, my daily column in Tehran Today was banned and in the end I had no job.”

This was also the year Farjami introduced Iranians to stand-up comedy, but he could not go on with his shows. There were red lines all around. For instance, satirists could no longer joke about the president or the government, like they used to do.

“I was interrogated by the Ministry of Information called Vezarat-e Ettelaat, more like the KGB. In May 2010 I realized I had to leave the country as soon as possible, especially when I was asked to go to The Court of Media.”

Farjami then went to Malaysia, where he stayed until 2014. During this time he got his PhD from the University Science of Malaysia, where he worked on his thesis about political satire in Iran. After he finished his education he had to leave Malaysia, but he went to Turkey instead of moving home.

Today YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are all banned in Iran, as well as the communication platform Telegram which used to be very popular among Iranians. The only social media channel open is Instagram, since people mostly post pictures there.

For the last decade the totalitarian regime has tried to squelch the laughter of the people. Still, Iranians tell jokes in their homes and among their friends. Satire and humor travel from mouth to mouth. The more taboos the Islamic regime imposes on Iranians, the more satires people make about them.

“There is no doubt that Iranians make jokes about Islam, the prophet, mullahs and religions, now more than in the secular Shah era”, which ended in 1979 with the Iranian Revolution.

Why risk everything?

His PhD thesis was about political satire as a journalistic genre in Iran since the latter days of the Qajar dynasty to the present, spanning more than a century. He interviewed 10 prominent Iranian satirists, only four of whom still remained in Iran.

The questions he tried to answer were: Why would someone produce satire, knowing that this act might have dangerous consequences? What motivates political satirists?

All of the meetings had to be arranged abroad. It took more than four years to complete the doctorate, which he started in Malaysia and finished in Belgium. The interviews were later translated from Farsi into English, to try to stay under the radar of the authorities, and resulted in the revealing publication “Iranian Political Satirists: Experience and Motivation in the Contemporary Era”. In this book published in the Netherlands in 2017, his sixth one, he told his own story as well.

In 2012, while he was working on his PhD, he received a Graduate Student Award from The International Society for Humor Studies for his research on political satire in the Iranian press.

I was awarded because my studies were not just done by an academic who chose this field. I was a political satirist who studied political satire.

“I was awarded because my studies were not just done by an academic who chose this field. I was a political satirist who studied political satire. It is very rare, because usually comedians, satirists or cartoonists don’t come to get a PhD.”

First class in stand-up

Since Farjami left Iran, he has concentrated solely on humor and humor studies. He arrived in Norway in June 2019, through the organization Scholars at Risk. At Kristiania University College, in addition to conducting research, he wrote and taught a course in stand-up comedy, looking at both practice and theory. This was the first time ever that stand-up comedy had been taught at an academic level in Scandinavia. Together Farjami and his class analyzed stand-up shows, and the students wrote and performed their own material – all in English.

“Did your Norwegian students give you a culture shock?”

“In some extent, yes indeed! The most notable was realizing how rational they were. I am not sure using the term ‘rational’ is proper for what I mean. I mean lack of fantasy, imagination … .”

Right before Oslo closed all of its venues due to the corona pandemic in March, Farjami did the first stand-up show ever in Farsi in Norway. He calls it a completely sexy stand-up show free from sexism. Before he moved to Oslo he did a show on media for BBC, filmed in London.

Unfortunately Dr. Oliver Double of the University of Kent had to cancel his visit to Kristiania University College in April, since the borders were closed. At this British institution people can get a master’s degree in comedy studies – learning to write their own material, engage an audience, make people laugh.

“Is there a certain formula for a good joke?”

In the set-up, you mislead the minds of the audience, and in the punch you present something unexpected.

“There is not just one formula, but to make it simple you have the set-up and punch. In the set-up, you mislead the minds of the audience, and in the punch you present something unexpected.”

“Can you please tell one of your favorite jokes?”

“Most of them are in Persian, but I will try to translate this one: Once there was an announcement for a circus in a newspaper. They were looking for a horse with amazing skills. This horse called and explained he really wanted the job. ‘Can you fly?’, the man asked. ‘No, I am a horse, of course I can’t fly!’ ‘Well, can you go into the fire?’ ‘No, I am a horse, of course I can’t go into the fire!’ ‘Can you walk on two legs?’ ‘No, I am a horse, of course I can’t walk on two legs!’ ‘Well, what can you do then?’ ‘Hello! I’m talking to you!’”

It has been a joy to have Farjami spread laughter on campus Kristiania. His last day is Friday 28 August. In September Farjami is off to a new position at OsloMet.

“What will you do there?”

“Hello! I will talk to them!”